Checkpoints, Teaching Theatre in Conflict Zones

Jessica Litwak

am at Gate C 63.

In the International Terminal at Newark Airport.

New York to Dubai

and from Dubai to Iraq.

The invitation to Iraq comes to Theatre Without Borders on a Wednesday afternoon. They need a Western theatre artist to come immediately to be one of the judges at a festival of theatre from all parts of the Arab World. Passports, visas, plane tickets have to be quickly arranged. Should I go?

Close friends, family and the US State department say NO.

“The Department of State warns U.S. citizens against all travel to Iraq given the security situation. Travel within Iraq remains dangerous.”

But I remember a desperate protest the night before George W. Bush gave the order to bomb Baghdad. I was on the Los Angeles streets with my children and hundreds of other sorrowful Americans wanting to bring some last minute sense to the power machine in Washington, cars honking, Republicans spitting at us. Later that night at approximately 05:30 Iraqi time or about 90 minutes after the lapse of the 48-hour deadline, explosions were heard in Baghdad.

Since then I have had a strong desire to enact some kind of a symbolic apology to ease a personal national shame for what my government did to Iraq over the course of two invasions, two occupations, and two wars. I didn’t ever I that imagine that art would give me the opportunity to take a small step to mend the footprint. But here it is.

The festival is the brainchild of Dr. Abdul Kareem Abood Ouda the Dean of the College of Fine Arts at Basra University. His mission is to bring theatrical and academic representatives from Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan and Sudan to Basra for a week of 13 plays judged by an international panel of theatre professionals. He says this event could never have happened during the occupation. “The occupation killed everything in Iraq. Before the occupation, the University supported the Arts. Now we have to work to bring that support back.”

I go to Iraq one cold November day from to New York to Dubai to Basra. At the Basra airport my hosts, my translator and several bodyguards in shiny suits who look more Italian Mafioso than Arab Soldiers meet me. A Sudanese theatre group from a University in Khartoum arrives on the same flight as mine. Security is high. Advised by Amir in urgent whispers I am to conceal my American citizenship by not speaking English in public, I am also warned to hide my female curves with large loose fitting clothing and head scarves, and most of all to hide the fact that I am Jewish.

The risk of kidnapping is high, and I am told in no uncertain terms that my kidnapping would be very inconvenient for my hosts. We travel in armed vehicles to our hotel. “This is a bad checkpoint” My host says, “cover your head, look down, don’t speak”. I don’t know what is “bad” about this particular checkpoint. None of them seem “good” to me. Every few blocks the car stops, the driver turns on the inside light.

A man in Military garb carrying a machine gun (there are so many guns in Iraq that they begin to look like toys) shines a light into our faces, asks for identification, the driver mumbles a greeting in return, waves a nervous salutation.

Streets are filled with tanks. Billboards line the street with photographs of martyrs, and wanted men. The wanted men are crossed of with a black spray painted X when they are killed but some of the martyrs are also crossed off with a black X. This is because they were martyred in the Iran-Iraq war, and the Basra government residing just 6 miles from the border with Iran, has demoted these martyrs to make amends.

This is life here. Everything is uncertain and everything is unsafe. No one seems to know who is in charge, who the gunmen are manning the checkpoints, or who the guys with guns are reporting to.

I sit in the middle on the back seat, not making eye contact, my bodyguard next to me. This particular checkpoint keeps us a long time. The soldier or who ever he is gestures towards me and speaks loudly in a voice that seems to get increasingly angry as the driver tries to negotiate safe passage. He wants my passport. I am suddenly afraid. Any thing can happen here. He takes my passport and walks way. My bodyguard takes his gun out of the back of his pants and follows the man with my passport. I wonder if I will ever make it back to New York. Then the bodyguard is running back towards to car shouting something in Arabic, which I assume, is, “Go! Go!”, because the driver hits the accelerator, the bodyguard jumps in to the moving car, my passport in hand and we speed off to the next checkpoint. Hopefully it’s not a “bad” one.

Sometimes it is hard to breathe on the streets of Basra. Dust is everywhere, dust that blows in from the desert, dust from the perpetual construction of bridges and buildings that are never finished, dust from the intense traffic, dust from the burning oil, dust from the rubble, dust as a constant reminder of war. The women’s faces are protected from dust with burkas and hijab the men wear scarves over their mouths and noses. When a deep breath can be taken, like out on the Tigress and Euphrates rivers, the ancient beauty of the city and the spirit of its people fill the heart and clear the lungs from Dust.

Basra built in 636 CE, is in the historic location of Ancient Sumer and the home of Sinbad The Sailor and the possible location of The Garden Of Eden. Basra suffered through the violence of Iran-Iraq war, The Persian Gulf War (“Operation Desert Storm”) the mass executions conducted by Saddam Hussein, and the most recent occupation by American and British troops that controlled the province until 2007.

In the hotel hallway after my bodyguard leaves me for the night, I go to the ice machine. A man appears out of nowhere. He approaches me quickly before I can open the door to my room. He grabs me with one hand and shoves me into the wall. With his other hand he clutches my neck in a stranglehold. He stops my breath. He leans his mouth to my ear and whispers one word: “America”.

The next afternoon all of the performers and the judges from the festival are on a riverboat on the Tigris River. We are on the deck after a large lunch of meat, fish, hummus and soft flat bread. My bodyguard follows me up to the very top of the boat where the young theatre companies have gathered to take in the view: Saddam’s abandoned yacht and palace, the submerged ruined boats along the river, the landscape of palm trees and far off oil fields burning, and the surrounding desert. The Egyptian company of actors begins dancing and chanting and singing regional folk songs. They are rowdy and proud, waving the Egyptian flag up and down to the musical rhythms specific to their country. They bring the women into the center— the Sudanese actress, the visiting scholars, and me. Their inclusion of the women in the dance is a kind of rebellion in a culture of gender separation and exclusion. We begin to dance with freedom and joy that rocks the upper deck of the boat. The bodyguard tries to stand close, but I leave his side to celebrate the fresh air streaming in from the music of voices and stomping feet. Suddenly, on the other end of the boat a group of Iraqi actors began their own chants and dances. A call and response between the two countries emerges. Competitive, fierce, a collective musical war of peace begins to shake the riverboat. “IRAQ!” “EGYPT!” “EGYPT!” “IRAQ!” A police boat follows close behind us. I think the music must have alerted the militia to some action of wild release. But a Syrian actor tells me the only reason the police boat is there is that there is an American on board. One American. The sound and movement is intoxicating, so alive that all we can do is clap our hands together and grin and sway. An elderly professor from Sudan grasps my arm and shouts over the music: "This is the only way we will unite the Arab world- with art."

While I am in Basra, Barak Obama is re-elected to the presidency. I stay up all night waiting for election results. Roberta Levitow is in constant contact with the State Department contact in Bagdad who is worried for my life, keeps texting me state-by-state election results. By early morning I know we have defeated Mitt Romney. When I come to the University the next morning everyone greets me with one word: “Obama!” No one speaks English, not even Dr. Kareem, but this word they know. They have informed me that they don’t like or trust my president, even though I try to explain to them, with the help of my translator, why he is so much better than they other guy. But this morning they have decided to humor me. They know I am happy and insist on patting me on the back and shaking my hand as if this is some personal victory. And it feels like one. My daughter sends me a text message containing President Obama’s acceptance speech. I show it to my translator and who passes my cell phone to a Palestinian colleague who speaks English. He reads the speech and bursts out with an emphatic shriek: I burst into tears. I am not sure why. I have never been patriotic and although I campaigned for Obama I am certainly aware of his faults and of political hypocrisy in general. But something cracks. The floodgates are open. I just can’t stand to by guilty and ashamed of being a white American one more minute. The panel of judges turned to stare at me. “ I am sorry” I sob, “I am sorry for what my country did to yours.” They cluck and shake their heads. An aging actress from Baghdad says in broken English: “But we love you, Jessica” they say, “You are not a bomb.”

The morning I am leaving Iraq, I ask Dr. Kareem, “What’s the next step?”. According to him, the next step is two-fold. First of all, he says, “Theatre needs to be brought to the streets so that it can be shared by all members of the community. “Intellectuals”, he claims, “tend to criticize and theorize. We need to take theatre to the average person.” “Secondly,” he says, “We need practical projects between the east and the west. It has to be collaborative. Practitioners are more important than intellectuals within nations in conflict. The media and politicians separate us. But if we communicate through theatre we can come closer to understanding each other. Theatre can serve as a medium to tear down stereotypes. We decided that I will collaborate with an Iraqi playwright on a play about Iraq and America. The fact that this writer is much younger than me, and a Muslim will make the collaboration interesting. Because it is not safe in Iraq, we will meet in Beirut to rehearse and develop the script.

There are 9 checkpoints on the way to the airport. In 4 of them I receive a full body search. The Basra airport must be the safest place in the world. The Sudanese theatre company that was there at my arrival is taking the same flight back to Dubai. The elderly Sudanese professor sits next to me on the plane. “We knew you were Jewish” he says out of nowhere. “It’s your nose that gives you away.” When the plane lifts off Iraqi soil he clutches my arm and cries: “We are free!” In Dubai at the most luxurious airport shopping mall in the world, I take off my headscarf and buy a glass of champagne and drink it out in the open.

Headed home to the west, my heart still in the east, the complicated division is just beginning. I will never again know which side I am on.

I am in the taxi on the way to the airport. (again) Worried. (again) About what I bring to this journey. I see my reflection in the taxi T.V. screen. Yup. Still a white girl.

I don’t want to be a white girl.

White skin. White heart. White Christmas.

I want the rainbow.

I want to change the world.

Lead the people to re-demption re-invention re-turn re-pair re-evolution. REVOLUTION!

WHOA! HOLD UP, WHITE GIRL! Who you think you are? Where do you think you come from? What makes you think you got the juice to change the world?

Did your people ride here piled together foot to head on a slave boat?

Did you get ransacked and murdered by pilgrims, massacred and strung up - your land stormed and stolen?

Did you do the Ghost Dance?

The Cakewalk? The Monkey? The Pittsburg Stomp?

I never wanted to be a white girl!

I wanted to be Patty Hearst, Dude.

I wanted to be kidnapped by a black Revolutionary.

Simbeonese Liberation Army.

Rename myself TANYA.

Be a Panther, and shit.

I grew up in the dream time. San Francisco. Summer of Love. Ashbury Street between Haight and Waller (sings:)

Take another little piece of my heart now baby.

I was a child of the revolution. (sings:)

We all want to change the world.

My mother sent me to a hippie school. Our teachers marched us into protest waving the Viet Cong Flag. (sings:)

And it’s one two three what are we fighting for?

I wanted to be an astronaut. Fly to the moon. In a spaceship.

I wanted to be a secret agent. Fly to Monte Carlo. With a jet pack. (sings:)

There's a man who lives a life of danger,

Or a Bond girl.

White Fur. White Leather.

I wanted to be an actor

New York City.

MY KINGDOM FOR A STAGE

White lights, white mask, Great white way

I am Emma Goldman in Union Square. “I believe in Anarchy, freedom, free love, speech. I believe in America, courage people pride I believe there is great work to do now however we can. .”

White Rap. Red sea.

I am Miriam at the red sea. “Come women. Shake your timbrels. Feel the drum beat. Place your feet in the mud of the sea bottom.”

We place our feet on the foggy beach.

White sand. White night.

Shout your truth so loud it stuns the treetops, child. You are enough. Be brave.

Woman I am, spirit I am, I am the infinite within my soul, I have no beginning and I have no end. All this I am.

Be naked with yourself, Girl. The eyes of the ancestors are upon you. White people.

Be proud. So I push two

White girls

Out of my tender womb and into the future.

And they will change the world.

I am at the Airport. Gate C36. JFK to London. London to Tel Aviv.

All my life I have wanted and not wanted to go to the place my Grandparents called The Promised Land. It has taken many decades to get me on this plane. But ironically when I first travel to Israel I on my way to Palestine. I am hired to teach and perform for the Freedom Theatre in Jenin. I have a brand new second passport, issued at steep cost by the U.S. government for “special circumstances”. My regular passport, stamped with Iraq, Lebanon, India, Egypt, and Jordan will cause me some uncomfortable interrogation, but more importantly once Israel stamps my passport many of those other countries where I work will not have me back. A clean passport just for The Holy Land.

In the Jenin refugee camp I was to lead drama therapy and psychodrama classes, theatre courses and puppet workshops for adults and children. I had told funders of my trip that Theatre skills are useful as learning strategies for change, and reminded them that art itself is a valuable tool. Because I told them artists are witnesses and chroniclers of their times. I told them that Theatre allows us to experiment, to succeed at not knowing, to fall, get up, fail and then as Sam Beckett put it, to “fail better.” The creative power of experimentation, would allow the participants of the workshops in the refugee camp to get up and fall down in new ways. I talked to them about moral imagination and paradoxical curiosity. I wasn’t sure if I was full of shit. But I knew I had integrity, heart, and now thanks to them, plane fare.

Whenever I prepare for a trip outside the relative safety and familiarity of the western world, I have to balance my natural anxiety with the real dangers present. In certain parts of the developing world, it is important to take precautions, but I am always fielding calls from concerned parties. As I always do I checked the State Department website and found certain travel warnings aimed at the two destinations to which I was headed. I found the following warning:

The Department of State urges U.S. citizens to exercise caution when traveling to the West Bank. Demonstrations and violent incidents can occur without warning, and vehicles are regularly targeted by rocks, Molotov cocktails, and gunfire on West Bank roads.

A Palestinian woman who was a potential participant in the workshops sent me an email:

Hello Jessica, I try see you in Jenin. I hope that the road will be more safe. Last week it was not safe at all. Hope meeting you, hope you be ok on the road. Rima.

When I asked my colleague at The Freedom Theatre about it, he replied in an email:

Jess, There are frequent road closures in the West Bank. Either because of protests and clashes with the army, or because of settler violence. The only danger is if you are in the frontline. Usually one gets wind of such an event and has to take a detour. This happened to us a few days ago after a performance... Life in the West Bank.

When I land in Tel Aviv, the lady at the border patrol asks me why I’ve come to Israel - Do I tell her I have come to combat the occupation- with something so dangerous I’ve had to sneak it on the plane: a weapon of peace and freedom: the theatre?

I made the long bus trip north. The first night in Jenin I wrote this email to my two grown daughters in the U.S. :

I am at the Jenin refugee camp – it’s 4 am- I am in a tiny room above The Freedom Theatre- very very hot here. But mostly there is noise. There is a mosque and Call to Prayer sounds close. Screaming boys throw rocks at my window and there are gunshots very close- apparently individual shots are infighting between refugee gangs - machine gun fire is the army. And there constant drilling – they are rebuilding the theatre in the middle of the night because it is safer to work then. The town of Jenin is a ten-minute walk from the refugee camp but it is not safe for me to walk there alone. Apparently it’s hard to get our workshop participants to come to Jenin refugee camp for because of the violence...feels a little like the South Bronx of Palestine. Tomorrow I teach a group of women in Nabulus, the next workshop is a group of social workers in Jenin, then a puppet, then a three-day workshop in Bethlehem, then an outdoor workshop in the Golan Heights and then a workshop in Ramallah. I have to lie beneath the window line because the gunshots are so close right now they threaten to break the glass.

In Shallah, (God willing) all will be well. Much Love, Mom

My very first full day workshop was with women in Nablus.

The Baby

All the women were wearing full-length coats and hijab in 100-degree heat, one older woman began the morning by making a loud announcement with glee. In one all female workshop the women were wearing full length coats and hijab in 100 degree heat, one older woman in her fifties entered the room calling out with glee.

FIDYA:

Ladies!

I am pregnant! I know, I know Habibti, it's hard to believe,

You look at me and you think she’s too old- FAR past childbearing years…

But Ladies Allah wants me to give my husband a baby boy.

You all know how I lost the last nine babies

PRAY! PRAY!

This one will be my healthy boy!

My husband is going to marry the second wife

So young, so tall- from Beit Jala,

I am lucky- you know Islam says he can have four and

All these years, so patient, he has only had me

if I give him a son, maybehe won’t do it.

I can’t stand it if he does.

It breaks my heart.

But I understand. I gave him nothing.

Only one daughter nineteen years ago,

but that doesn’t count, .

Lady Teacher, I have to leave class before lunch

to see the doctor

make sure everything is good.

I have lost 9 babies but this one -

I can feel him inside me.

My healthy boy.

She returns to the workshop just after lunch. She crumples onto the floor, sobbing.

FIDYA: The baby is dead!

The doctor found no heartbeat, now she has to go through a surgery. The eighteen other women all began shouting at once. I bring them into a circle. I ask Fidya to come into the center of the circle. I ask each woman to say one supportive thing to this devastated woman. Every single woman says a variation of the same thing:

I hope God saves your baby

Inshallah you give your husband a son.

God willing you can make for your husband a baby boy.

Inshallah you save that baby for your husband

No one says:

Take care of yourself.

You already have a daughter. Cherish her.

I hope you feel better. Eat some lunch.

Inshallah your husband is kind to you.

The woman weeps harder in the center of the circle, clutching her belly, rocking back and forth, tears streaming down her face. They keep at her- Inshallah the baby boy. I want to scream at the women but this isn’t my business. This is not my culture to correct or change. I am a visitor. A white girl. It is not my place to rail with western feminist patter against “gender bias”. I can only support this woman to become stronger and more self-loving. But how? For a few minutes I feel lost. Then Augusto Boal comes into my head. “Truth is therapeutic” Boal whispered in my ear “Jessica, this human being needs to be seen holistically, so that humanity’s “tragic passion and clownish love” can exist.” So, I decide to see if it is possible to find the other side of the coin for this woman. I engage her in a psychodrama in which she recounts a time when her daughter was small and had been lost in a huge mosque during an attack by Israeli soldiers. The dramatized reunion with her daughter made this woman realize that her grown child was someone she could hold onto and be grateful for. She hugged the woman playing her daughter and held her tightly. She wept but these were tears of gratitude. I asked her what she was going to do when she left the workshop.

FIDYA: First thing? I am going to call my daughter.

Watermelons

When flag waving

is outlawed by the Israeli government,

the Palestinian youth in Jenin carry

watermelons

And smash them on the ground.

A broken watermelon is red and black and green-

The colors

of the

Palestinian flag.

This is theatre at its best- the physical metaphor of true resistance.

The children in the refugee camp play and shout late into the night outside my window. The gunfire doesn’t seem to bother them. One morning I gather them together I tell them we are going to make puppets to make puppets.

One of the men at the theatre buys ten brooms and cuts up the Broom handles to make the puppet bodies. He helps me find Newspapers, glue, paint, brushes. I walk into Jenin – now I feel comfortable walking alone. I buy buttons, ribbons, and pieces of bright fabric.

The children first write or draw their secrets, the things they keep in their heads – the dreams and wishes, the memories, the stories they tell no one. Some of them agree to share these, others keep their papers to themselves. The bad things we decide to throw away and later we put them on the fire. The good things we build into brains. And the

Brains become the core of the puppets heads that the children then build and paint and decorate and use to perform.

At the workshops the Women and The Men tell many tales of small rooms and soldiers, of sorrows and goodbyes…

The night the Israeli army took my father… When the Israeli army took my son…When the Israeli army took my husband…

If I had known you ten years ago I would have killed you… Why? Because when the Israeli army came to arrest me, my 8-year old sister answered the door. The soldier shot her in the face. But now I have grown up. I have changed. Now I know that not all Jews are bad. Not all Jews would kill your sister.

We made scenes of rage and redemption, sculptures of anger and release.

The Bug

This student is a man in his thirties who wants to be a social worker. He is hoping drama therapy and psychodrama will be useful. A few months ago he was released from an Israeli prison where he had been for 2 years.

I ask him to tell me about his cell. He can’t remember it. As hard as he tries he is not able to see the walls or the ceiling or the floor or the tiny barred window or the hole in the ground or the thin torn mattress. He knows these things were there because his brother and his father have also been in jail and they made a portrait for him. It deeply disturbs him that he can’t recall.

Do you remember anything at all I ask him.

One thing, he says. An insect.

What kind of insect?

A black beetle. I trapped him under a plastic jar and kept him there to be my friend. I talked to him for nearly a week before he died. I even shared crumbs from my bread with him. But he didn’t make it. I’ve never told anyone this. I ... Named him. Ali.

Let’s try something I said. You want to try something?

Yes he said.

The translator sat beside me on the floor.

Let’s imagine. Imagine you are the bug.

He closes his eyes and moves slowly down the corridor of his imagination. Until he is inside the beetle.

Suddenly from the beetles perspective he can finally see the room. The stain on the floor, the crack in the wall, the bars on the window, the mattress and the hole. He opens his eyes, weeping.

Are you OK?

Yes. He says. It’s better to see.

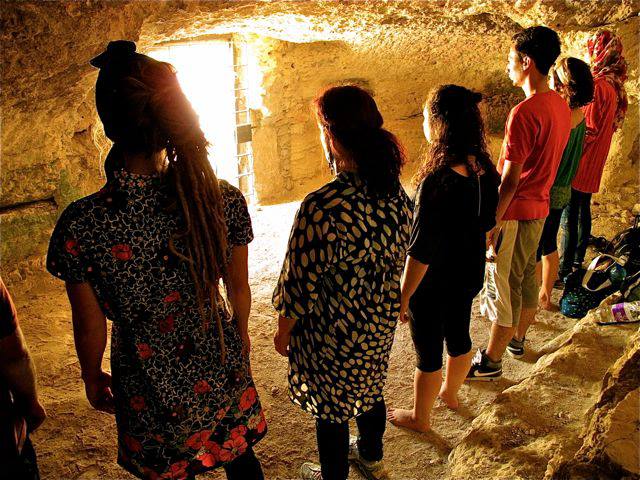

My colleague and I leave Jenin on our way to Jordon and from Jordon to Cairo where will teach theatre, Playback and drama therapy workshops. We pass though the checkpoint. The checkpoints between Israel and Palestine are territory that is not easily imaginable by Westerners. One either drives or walks through a series of barbed wire enclosures. You are either body checked if you walk through, and driving through you are subject to random full car searches where all of your belongings are removed from the car and transferred to a search station by shopping cart, and an explained gas is pumped into the car by a long tube, supposedly a method for finding explosives. At one point during a frightening, long and frustrating search of a car I was driving with a Palestinian actor form the Freedom theatre, I shoved my American Passport in the Israeli soldier’s face and said irately “I am an American! Stop this at once.” They laughed at me, and then confined me to a small cell for the good part of an hour. Which is nothing compared to the days spent in prison or in small rooms waiting for visas that Palestinians endure. Still I wonder if will we miss our flight from Amman.

I eventually fly home.

Cairo to Paris. Paris to New York

Jetlagged, I am lonely for the Middle East.

In the cab on the way to my apartment I think I might be crying.

The taxi driver offers me a tissue.

Shukran,

I say.

He smiles at me.

An Arab immigrant, he thinks I am being friendly.

Actually, I just forgot where I was.