Devise Theatre, Repair The World

Why Devised Theatre they ask? “They” are the funders. “They” are the scholars. “They” are a new generation of theatre makers just beginning to identify themselves as devisers. Why fund Devised Theatre? Why call it Devised Theatre? Why make Devised Theatre? My answer is this: Devised theatre must be funded, named and made because it can repair the world. Is this a simplistic, reductive, idealistic statement? Perhaps so, but I believe that theatre, if conceived with moral imagination and strong leadership can lead to positive change. Person-by-person, community-by-community, theatre as a collective art form can transform conflict and increase good communication, mental and physical well being, personal freedom and self-esteem. To devise something together a group needs to work collaboratively, which necessitates listening, seeing, and understanding each other. Collaboration means tolerating, and even embracing the paradox that people encounter during the intimate exchange of ideas. By making art collectively we are practicing how to live collectively. In our diverse unity we are exploring the very basis of peace building. And if the process affects the product, we are producing meaningful art that serves a community of artists and will be useful to a community of audiences as well.

The only way I personally have been able to effect change in the world is though theatre. As an artist-activist-scholar my work is devoted to the exploration of theatrical practices for social change. This is the formula I use to devise.

Fig 1. Art, Activism, Scholarship

What is Devised Theatre they ask? I am part of an older generation of theatre artists who are suddenly wondering how to explain what means to devise when we have been devising organically throughout our careers, some of us knowing no other way of cooking a theatrical meal.

If we define Devised Theatre in academic terms and become experts in its intelligent classification, renaming it something like “Performative Devisement”, and explain its attributes and pitfalls in multi syllabic conceptual phrases that require dictionary reference, will we be able to capture the experience of artists and audiences? If we achieve definition and can apply for grants based on descriptive perfection, must we then keep making sure to refine and re-define Devised Theatre over and newly again say, annually, so that it always sounds fresh and complicated like an evidence based science that only a very clever few could really comprehend? Or shall we just have to admit to making collaborative theatre created in a variety of ways in rehearsal rooms where every technique is tried and where everyone gets a say in the process.

The H.E.A.T. collective www.heatcollective.org is the theatre company I founded that focuses on devised theatre for personal and social change. H.E.A.T. is an acronym for Healing, Education, Activism and Theatre. At the intersection of performance, drama therapy, research, and human rights, we offer workshops in performance and peacebuilding, playwriting, voice, ensemble building and puppet making, we explore how devised performance can support communities and individuals.

Fig. 2. The H.E.A.T. Collective

What is devised theatre? There must be an historical context. In the beginning God devised the heaven and the earth in collaboration with various players, including Adam, Eve, a snake, a tree, and a Big Bang…? Perhaps devising isn’t Biblical in origin, but it certainly is an historical practice. Long ago, even in the theatre (where ego threatens to reign supreme) theatre was collaborative and devised. The playwright wasn’t a Royal. The script was not a holy scroll. Even Shakespeare tore his plays into pieces and handed them around the room. Directors didn’t even really exist until Freud came along and gave us Oedipus complexes and we decided someone should be running the show. Before Freud actor-managers would make sure that no one bumped into each other, or insist (as Sarah Bernhardt did one night) that everybody do the show (Camille, in her case) in the nude so as not to upstage each other with costuming. But still people worked more or less in ensemble and although there was a script and a producer and a bit player and sometimes a dog, the assumption was that everyone was there for the same purpose. The play was the thing, and the play was devised (invented, planned, developed, formulated, concocted, conceived, contrived, worked out, thought up, created) by every single soul in the room.

I am always first and foremost a theatre deviser, although my roles on any given project may differ. I am sometimes a director, more often an actor, when necessary a producer, but I identify mainly as a playwright. I am educated as a playwright and have written 27 plays, most of which have been produced. So I am writing about devised theatre mainly from the perspective of a writer, someone with the point of view that on every theatre project there needs to be a playwright, or a dramaturge or any human of any title or no title at all who is charged with caring specifically for the words.

I am about to start work on a new devised project about poverty in America with a group of felloe theatre artists. We are a director, a composer, a choreographer and several performers and I, the playwright. All the roles are clearly defined. And yet this is billed and funded as a piece devised theatre. What makes it thus? Is it the many collaborative conversations that go into the work, brainstorming sessions that effectively shape and construct the work? Is it the shared source material that is passed from hand to hand? Is it the reliance on rehearsal as a means of script development? Is it the presence of improvisation? The inclusion of actor generated research? The exchange of theoretical ideas shared so that we can build a joint vocabulary? In a devised process the playwright is not sitting alone in a room devising by herself. She is writing, and then disclosing, then improvising, then discussing, then writing, then more imparting and brainstorming, then throwing out what she has written, more writing, and the spiral of action continues until an audience is invited and even then the devising continues, and creation ebbs, flows, blossoms, fades and finally explodes.

In this process I will conduct interviews with rich and poor in the Northeast, I will craft monologues based on those interviews, we will put some of those to music, and play with actors and singers in space. The more I release a sense of ownership the better the piece will be. The more the composer and I meld our gifts, the more interesting and striking the result. This is not the business savvy way about going about things. My agent would prefer that I keep the monologues and scenes separate so that authorship will be a cleaner and less litigious circumstance. But this group is made up of old time devisers; we are hungrier for community and artistry than we are for ownership.

I came of age as an artist at the Experimental Theatre Wing of NYU when that department was just a nascent body of players, a collection of seekers and makers, students and teacher-students, smokers and non-smokers, meat eaters and otherwise. Not “actors” or “writers” or “dancers”. Just artists. Sometimes Lee Breuer convinced us to gut and paint a storefront, sometimes Spaulding Grey made us talk about our childhoods, sometimes Anne Bogart convinced us to stay up all night in character on the D train. But mostly we were just making stuff together over and over and over – in basements, on rooftops, at The Public, or at La MaMa, or in Washington Square Park.

We grouped ourselves into ensembles called “ Redwing Theatre”, or “Undercurrent Theatregang” or “Mabou Mines”. Many of us had no designated playwright or director and we rehearsed collectively for months at a time and built everything from the ground up. We marched into the street when Harvey Milk was shot, we shut down the studio when John Lennon was shot, we made plays in reaction to everything we read, listened to and experienced from Joan of Arc to Janis Joplin from Tourism to Stonewall, we re-wrote Chekov and reimagined Gorky. We didn’t have resumes and we didn’t read the trades, or go above 14th street. We made theatre pieces that we thought would change the world. No matter what our role in any particular piece might be; our dedication was life and death important. We were devising our work our lives with passionate intensity. Even our solo shows were group efforts. We felt ownership for our craft and our community and did not seek ownership for our words or works. We were on fire and undefined.

Moving into present tense, I realize that not all theatre is devised and not all theatre artists think as communally as we did when we were coming of age in the 70’s and 80’s of downtown New York.

I realize Devised Theatre is form of creativity that may need definition in order to be preserved, continued, reawakened, and yes, funded. So here goes:

Devised theatre is a theatre in which genius is a collective paradigm. It is a theatre where magic happens not because one person is brilliant but because all people are open to brilliance. I saw a sign on a subway platform that said: “Imagine what you could accomplish if you didn't care who got credit.” A deviser conceived that sign, or a group of devisers in collaboration.

Good collaboration depends upon the presence of justice and creativity. “Just Creativity”, like “Just Peace”, is a notion that contains paradox. Creativity (like peace) is not a product that can be separated from its process. Although in the theatre we often focus on a creative product, the process is always obvious- at least subliminally so. For, even if the two stars hated each other and are still very good together in the climactic love scene, and even if the director was a bully and the staging is still fantastic, and even if the playwright is a narcissist but a still great poet, the audience will feel on some level the lack of collaboration, the lack of devising, the lack of justice. Ego will reign supreme even though the audience might enjoy the play or be frightened by it, even possibly never forget it, it won’t open their hearts and fiddle with their souls in the same way a devised collaborative peace will. The collective experience of the artists trickles down to the audience. Although an audience might never know collaboration was missing from the process when viewing a brilliantly performed and beautifully stage well written play, but they sure will recognize it when it was present. The collective collaborative devised spirit will inform a play with the music of unity and the magic of ensemble. You can smell it in a curtain call.

The first necessary attribute of Just Creativity is Generosity. Amish barn raisers have taught me quite a bit about the art of collective collaboration. The basic reality of barn raising is this: If the Johnson family asks the Armstrong family to help them build their barn, the Armstrongs will show up at the Johnsons with bells on. They will bring hammers and nails and baskets of food, and spend as many days as it takes cheerfully spend their sweat equity pounding nails and hauling wood and feeding and organizing until the Johnsons have their completely finished beautiful new barn. The Armstrongs can give their time and energy fully and enthusiastically because they know without a doubt that the Johnsons will just as happily do the same for them. The Amish live in collective communities that function because of collaboration. I have brought this concept to theatre communities, working to encourage people to put passionate focus into each other’s ideas. The practice works especially well in the community of a company working on a theatrical project. People raise problems and for 15 minutes their issue is the center of focus and everyone pours their best brainstorming and their resources into that problem. Then the attention switches to someone else. It is amazing how creative and generous people will be when they can trust that they will be the recipients of the same generosity. The eager exchange of energy becomes a fertile ground for devising, as the collaborative process requires profound trust.

The second attribute of the Just Creativity necessary for Devised Theatre is Paradoxterity:

There must be tolerance for difference present in a collaborative rehearsal. Not just cultural diversity, gender diversity, age diversity, but also the diversity of approach. People create differently. I teach an acting workshop in which I focus on three ways of approaching the art of acting. I call it the Three Actor Paradigm based on the styles of three nineteenth century actresses. The work focuses on CRAFT (Developing the actor of precision through clarity of voice and speech, movement and expression) as demonstrated by the work of the actress Ellen Terry CREATIVE RISK (Developing the actor of ideas and vision through character work and composition) as modeled by the actor Sarah Bernhardt, and TRUTHFUL EMOTION (Developing the actor of authenticity through kinesthetic, psychological and emotional spontaneity and moment by moment action / reaction) as exemplified by the work of Eleonora Duse. I ask my students to identify which approach they are most comfortable with, which on is the biggest stretch, it is important for an artist to understand how s/he works and to know how others see a creative challenge. We can talk about Merging theories and practices of classical acting, experimental performance and method work, students and attain a toolbox of skills for future exploration and mastery, but first we must learn about our own perception and how to be tolerant when someone else’s creative view differs from our own.

Fig. 3. The Three-Acting Paradigm

I began to think of the work around the paradox of creativity as training for dexterity I call Performative Paradexterity. When working with socially engaged theatre to initiate and nurture change, cultural and personal paradoxes arise. In this process all paradox is witnessed, met with curiosity, then creative paradoxical dexterity is practiced through inclusive theatre, drama therapy, and ensemble building techniques. The goal is the creation of meaningful art and brave ideas that inspire transformation of conflict and the emergence of vibrant community conversation.

“Creative conflict” is a term often heard in conjunction with “creative differences” to explain the impossibility of collaboration between artists. It is a term that generally means, “We can’t work together”. I want to use it in a different way, not as a noun but as a verb. To engage is conflict creatively means to move through the tough issues with art. By facing the glitches, and the troubles, and the misunderstandings, brave participants in the process can resolve issues without avoiding them. I am not talking about a therapeutic process (although the tools of drama therapy are helpful in this case) I am talking about a fully engaged artistic practice that enables artists and audience alike to embrace paradox and move towards real personal and social change.

The third important attribute for Devised Theatre is Useful Content.

Devising collectively gets the stories that need to be told, told. The theatre must reflect and communicate issues of community. What issues are there but issues of social justice, the voice of the people, the pulse of the world, the heartbeat of civilization? If we are not making the theatre that needs to be seen and singing the songs that need to be hears, why are we making and signing? Theatre is service. It must be important to those who will witness it, and it must be, according to one of our iconic devisers Bertolt Brecht, useful. The only way to make a piece of theatre that is useful to nearly everyone in the audience is to make a piece of theatre that is useful to nearly everyone in the rehearsal room. The only way to know if the play is useful to its own creators, and thus useful to the people who will witness and experience it, is to devise it … together.

Three Examples of Devised Theatre:

The New Generation Theatre Ensemble:

Pure Ensemble, Devised Theatre with a Playwright in the Wings.

I started N.G.T.E. when my daughters were young. We had moved from Los Angeles (where I had been a screenwriter, a playwright- performer and a tenure track theatre professor) to upstate New York where I had taken a job running a K-12 drama program in an alternative private school. In Los Angeles my elder daughter had undergone major brain surgery and I no longer had the time or the will to spend the majority of my time in hot pursuit of a hot career.

At the private school I taught creative drama, acting and playwriting to students of all grades and I directed original curriculum- based plays. Some of the parents at the school asked me to start an after school program for the talented theatre kids who wanted to go further with professional level training. So the original notion for NGTE was a pretty straightforward teen theatre-training program. But as soon as I started setting up auditions and venues, I began to see a different sort of opportunity.

The auditions for NGTE began to attract a diverse group of talented youth from a large variety of neighborhoods and backgrounds and ages. I enrolled them all. NGTE became a company that championed diversity above all else: economic diversity, ethnic diversity, gender diversity, diversity of sexual orientation and age diversity. That first year we had a 10 year old and a 19 year old, the next year we had a 12 year old and a 25 year old.

The outreach flyer read. “The New Generation Theatre Ensemble a Teen Workshop and Performance Experience for serious theatre students. It is an exciting and fun theatrical course and rehearsal process, which is run as a theatre company in the ensemble style. At NGTE young people attain skills and experience through professional caliber training in acting, voice, movement, playwriting and improvisation. This is an exciting theatrical forum where young people attain skills and experience through professional caliber training in acting, voice, movement, play writing and improvisation. Each year culminates with an original devised theatrical production created by the company.”

The central mission of company was to A) build community and create a company while B) teaching theatre skills and C) creating an excellent and completely devised original show. The mission was divided evenly between three practices: Training, Ensemble, and Production.

Fig. 4. Training, Ensemble, Production

The ensemble was formed consciously. A buddy system that included having big and little brothers and sisters, and engaging in weekly exercises just with and for your buddy of the week (i.e.: bringing your buddy a surprise gift, asking your buddy for help with something, making an art project with your buddy, etc.) helped the process. I interviewed kids and let them know how important the sense of ensemble was to the process. If they joined the company they signed a No Gossip Clause which meant that they agreed not to gossip about anybody in the company for 8 months. They could gossip about anyone outside of NGTE but none of there company members. This was to avoid what I call Gossip Bonding, which is rampant not only among youth but also among adults. Gossip bonding is the shortest and easiest pathway between two people in the process of bonding – the easiest and quickest way for me to bond with Sarah is to talk about the infractions of our boss Daisy. The fastest and surest way for me to bond with Bob is to say something damning about my difficulties with Joel. The soundest way to get a person on your side is to quickly find a common enemy. Finding a common pastime, or a shared favorite food or to combine praises about a third party takes a little longer and is harder to do. But I insisted on it in NGTE and soon people in the company began to relax, trusting that no one in this particular room was going to talk mean behind their backs.

NGTE at its height was a splendid example of devised theatre. At the beginning of each year in early October, we would train for about a month. The youth developed text and characters; embraced the rigorous training and developed skills in voice, movement, improvisation and scene study.

After our training period, each rehearsal would include some form of investigation about whatever the issues were on everyone’s mind. Brainstorming sessions helped the company decide what the subject of that year’s play would be. This was a collaborative process, guided and directed by myself, the master teacher and assisted by one or two other adult interns. Sometimes I came into the process with an idea (fairytales or the history of war, etc.) and other times the idea was discovered through a series of exercises, part theatre, part drama therapy, part ensemble building, designed to discover the open tension systems in the group. The exploratory exercises created a community spirit and information organically emerged about what social questions most needed to be asked, and what kind of play the company most needed to make.

Once the subject or theme was decided, I would focus on character building, improvisation and scene work, based on the company’s research into the theme. We created many original plays from classical texts that either reflected the current curriculum some of them were studying or the current issues in their lives. During a school year devoted to medieval studies, which some NGTE kids were involved in we worked with The Canterbury Tales as source material. In our version, Postcards From Canterbury each student researched a pilgrim and created the character as well as researching and creating period dances and songs. The following year when a group of the company members were studying Greek history and culture we did a version of the Odyssey. During our play Sea of Troubles, The Long Journey Home the audience followed Odysseus on his journey in a site-specific moving play encountering Cyclopes and lotus-eaters. We did a piece that explored Midsummer Night’s Dream (set in the bushes of Central Park) In another season we investigated the concept of gang wars and bullying using Romeo and Juliet as inspiration. Our play Verona High we looked at the issues through the eyes of two suburban gangs, one rich one poor (which division basically reflected the make up of the company).

In the process of developing our play GRIM students would research, interpret and improvise each of Grimm’s fairytales, developing ideas as homework and they would bring in scenes and folk songs from their varied cultures. We approached Grimm's fairy tales by delving into seven of the original fairy tales and setting them in a contemporary urban home.

For The Moons of Jupiter each company member taught a science class, for War an American Dream company members interviewed people (like a War reporter, a soldier, a peace activist) and researched different periods of history in study groups. . In War, An American Dream the company looked at the history of war in America with choral poetry and through the eyes of three families, one White, one Latino, one African American. One of the students passed her history regents exams with flying colors due her research for the play and her embodiment of characters throughout American history.

The story would form directly out of this period of discovery, which would take us up to the winter break. During the break I would take all the improvisation, research and discovery material and craft it into a script. When we would come back in January, we would begin rehearsing and rewriting the script. The staging began and we culminated the year with a series of performances in May. The 8-month progression of devising the project was an ensemble effort. Although I was the lead teacher, writer and director, everyone had input and a say in the process and a hand in the product. This collaboration was made possible by our intensive focus on community building.

In NGTE all the plays were ensemble plays, the plays were written with the dual goal of making great theatre and democratizing the company. There were no big and small parts, sometimes a character would advance the action of the play or be at the center of a conflict or the main fulcrum of a story but there were no “leads” and “supporting roles” everyone may not have had the exact same number of lines but they had the exact same number of moments and same amount of spotlight. At times I chose roles for actors and talked to them in depth about why they were getting that particular role, but more often than not, the plays were self-cast by the company that seemed to organically understand who should play what. If someone felt unhappy with his or her part we would look at the reasons why and decide together if it was a personality issue or a theatrical one. We worked through the issue together. Whenever we could, we wrote the part that the company member needed (and eventually wanted) to play. An interesting side note about casting: the actors that later played the same parts weren’t always as deeply connected to the role, and a different sort of process was necessary. Devised theatre is created collaboratively but the scripts that emerge from a devised process but then go on to be performed by theatre with a traditional casting and rehearsal process (The Laramie Project is a perfect example). Several of the NGTE plays (including Sea of Troubles, Postcards From Canterbury, Grim and The Moons of Jupiter) have gone on to have high school, college, and Equity professional productions. Auditions were held, and the director decided on the casting. I co-directed a production of The Moons of Jupiter at a university where the casting had been decided by other faculty members before I arrived. They knew this pool of graduate students much better than I did. When we developed the play at NGTE four young women had been chosen (by the company) to play four scientists from history: Galileo, Newton, Darwin and Einstein. They immersed themselves in research, taught us science lessons, and developed the characters with gusto, and the task of shifting gender for the roles was a big part of the adventure. But when casting was done at the university, the woman who played Darwin felt frustrated to have been cast as a male. I found this out midway through the process when recasting was too difficult to orchestrate. She had been playing men since matriculation in this program and she wanted to embody the role of a woman. But the casting process (as with most traditional casting processes) did not allow for actor feedback in relation to choice of role. These graduate students had been used to devising their own work, and felt somewhat trapped by choices being made for them by theatrical authority figures. As an Equity actor I have certainly experienced my share of auditions, and lived in the realm of traditional process: directors and playwrights and casting directors and producers matching actors with roles. I have also written parts for myself (and cast myself) in four solos, a duet, a trio, and a large ensemble piece.

When I started working with teenagers, I wasn't sure what to expect. I knew I wanted to do it because of my own history as a disadvantaged teenager whose life was saved by theatre, but I wasn't exactly sure what we were going to create or if I was even going to survive the experience. But what followed astounded me. The student actors worked in a supportive and collaborative environment to study and develop original work. The unique voice of each student is cultivated and encouraged to shine. Those who are more interested in movement, music, writing or technical theatre are supported and given experience in that chosen discipline. Our Motto at NGTE was: Divine Mischief. Divine Mischief meant that we had deep respect and reverence for theatrical art, history and education while embracing every possible moment of creative fun theatre can bring. Together each year the company wrote the mission statement. One year’s statements reads: “Great Theatre is Generous. Theatre exists to inspire others and improve the world. Great Acting means to be true, brave, and free. A Great Company supports the uniqueness of each individual while keeping focus on the group as a whole.”

The company met each Tuesday and Sunday afternoon from September through May and culminated in a May production in New York City. Some remarks from youth over the years: “I loved the process of developing character through improvisation and being part of an ensemble of great kids.” "Through NGTE I have learned to be more open with myself and others around me. Through this experience I have met amazing people and hope that I will share many more memories with them all", "This experience at NGTE has been so wonderful. Everyone in this company came the first day eyeing each other cautiously and looking around quietly. But after working together for so long, all the members in this company have grown so fond of each other and we are now able to laugh and act as a company", "From this experience I've learned how to push myself to the furthest of limits and come out strong, confident and successful. Working with these amazing people for 8 months has been the best experience in my life. I have come to know and love 12 people who have changed my life, helped me and accepted me. I have also learned to get over my stage fright which is one of the reasons I joined."

During the eight years of NGTE, the devised theatre was very pure because we did it over and over each year and began to share a common vocabulary of devising and collaboration.

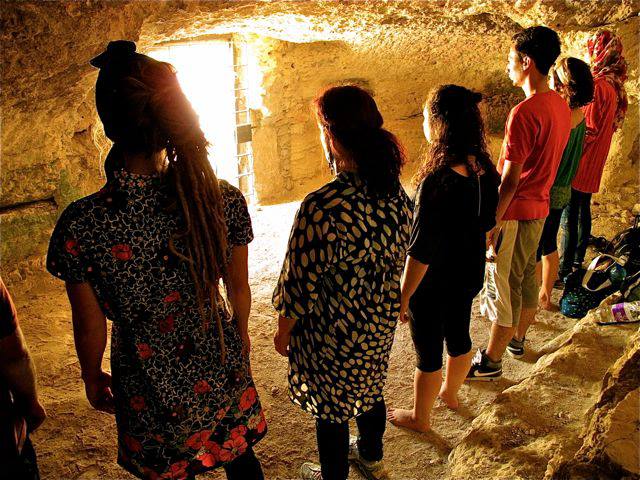

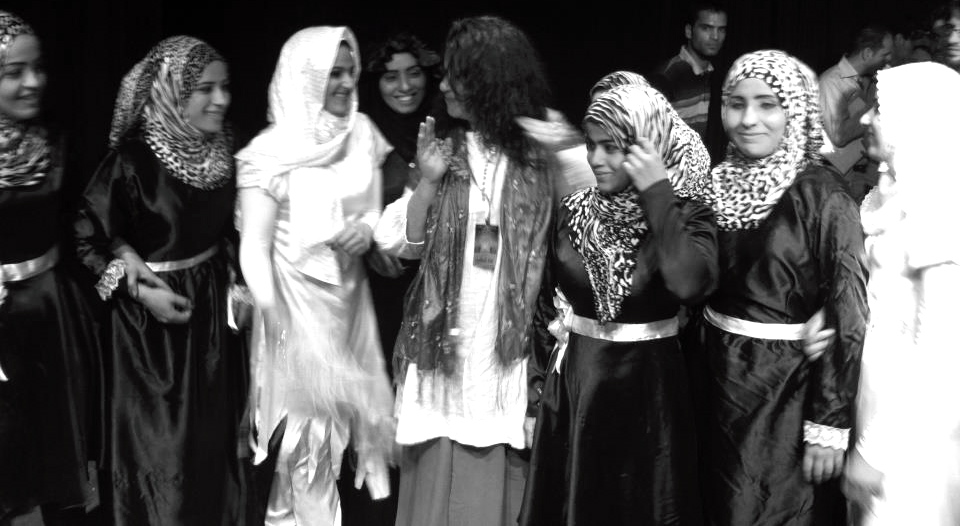

Fig. 5., Fig. 6., Fig. 7., NGTE Photos

Dream Acts: Five Playwrights Devising One Script

Dream Acts was the brainchild of a playwright who brought me into the process along with a director. We were concerned about the inability of congress to pass the Dream Act (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors, S.1291) the controversial proposed federal legislation known which had been first introduced in the Senate in 2001. The Dream Act was conceived as a way for undocumented immigrants to receive specialized assistance related to attending colleges and universities in the United States. The students around the country championing the Dream Act are known as “dreamers”. We wanted to devise a theatre piece that brought awareness to the voting public about the pending legislation, and support the work and lives of the dreamers.

The three of us brainstormed about the project, we then met with high school teachers in Queens who had classroom filled with immigrant students. One teacher told us that 60 percent of her New York classroom was undocumented. This teacher related many stories about her student’s daily struggles with their undocumented status and the prejudice they experienced. I recall one honor roll student being told at a job interview when he could not produce his proof of citizenship, “What a surprise you don’t LOOK undocumented”. As we heard these stories we clarified our purpose to devise a collaborative piece that would shine light on the plight of these young people. We gathered together three more playwrights so that we had a collective of five writers of different ethnicities. We then organized workshops with undocumented teenagers and identified five specific issues that they faced, defining five different aspects of the Dream Act. We settled on five nationalities: Mexican, Jordanian, African, Ukrainian, and Korean. Then each playwright pulled a Dream Act issue and a Nationality out of a hat. So the White writer got Mexico and Deportation/Detention, the Japanese writer got Africa and culture/assimilation, the Romanian playwright got Jordanian and legal issues, etc. Each writer wrote a short one-act play and then we created some interwoven scenes and dialogue and some choral pieces that tied the five stories together. After rehearsals and readings, the play opened in New York. In the play Dream Acts, five undocumented students from Nigeria, Mexico, Ukraine, Korea, and Jordan relate stories of their extraordinary challenges in living ordinary lives under the Homeland Security radar. Each story is moving and urgent; some are funny, others are tragic, and through their experiences, we learn about the DREAM Act and the secret lives led by undocumented students.

The first run of performances included several post show panel discussions. The play has since been performed at colleges around the country, and is always followed by discussions and panel discussions about the Dream Act, undocumented immigrants, and the role of theatre in fostering social change. The play was co – conceived and co-written, devised by five writers, five actors and one director. In the final play the five short pieces were seamlessly interwoven so no audience member could distinguish which playwright wrote which part. So although the script came before the rehearsals (the opposite order from the NGTE process) the creation was built cooperatively and was a true collaboration.

My Heart is in The East: One Playwright Devises a Script

This is the most traditional example of theatre making I will offer here. I include it because I think that devising occurs in the most unlikely places including in the traditional solitary act of writing a play. When I got stuck in the process of writing the play and really didn’t know whether to go one way or another, use one version or another based on the responses of a director and a producer who were interested in bringing the play to production, people were surprised at my emotional reaction, and my heartfelt confusion about rewriting. They asked me, “Why do you care what anyone thinks? It’s your play!” But I didn’t believe it was just my play. I am a deviser not a novelist. A play isn’t a play like a short story is a short story. A play is only a play when it meets with collaborators who will bring it to life on the stage. Without collective devising a play exists (like a short story) on paper but not in its truest form. A play has is not written to be read, it is written to be heard and seen. `So a play on paper without its collaborators (actors, director, designers, producer, venue) is not fully born. Yes, I cared what potential collaborators said, in my mind, it was their play too.

Fig. 8, Fig. 9., Fig. 10 Photographs from My Heart is in the East, La MaMa 2015

The chronology of a script

I worked on this play for about three years. Some of the pieces in it were inspired by my travels and experiences in 2012-2013 and I wrote them as monologues during that year.

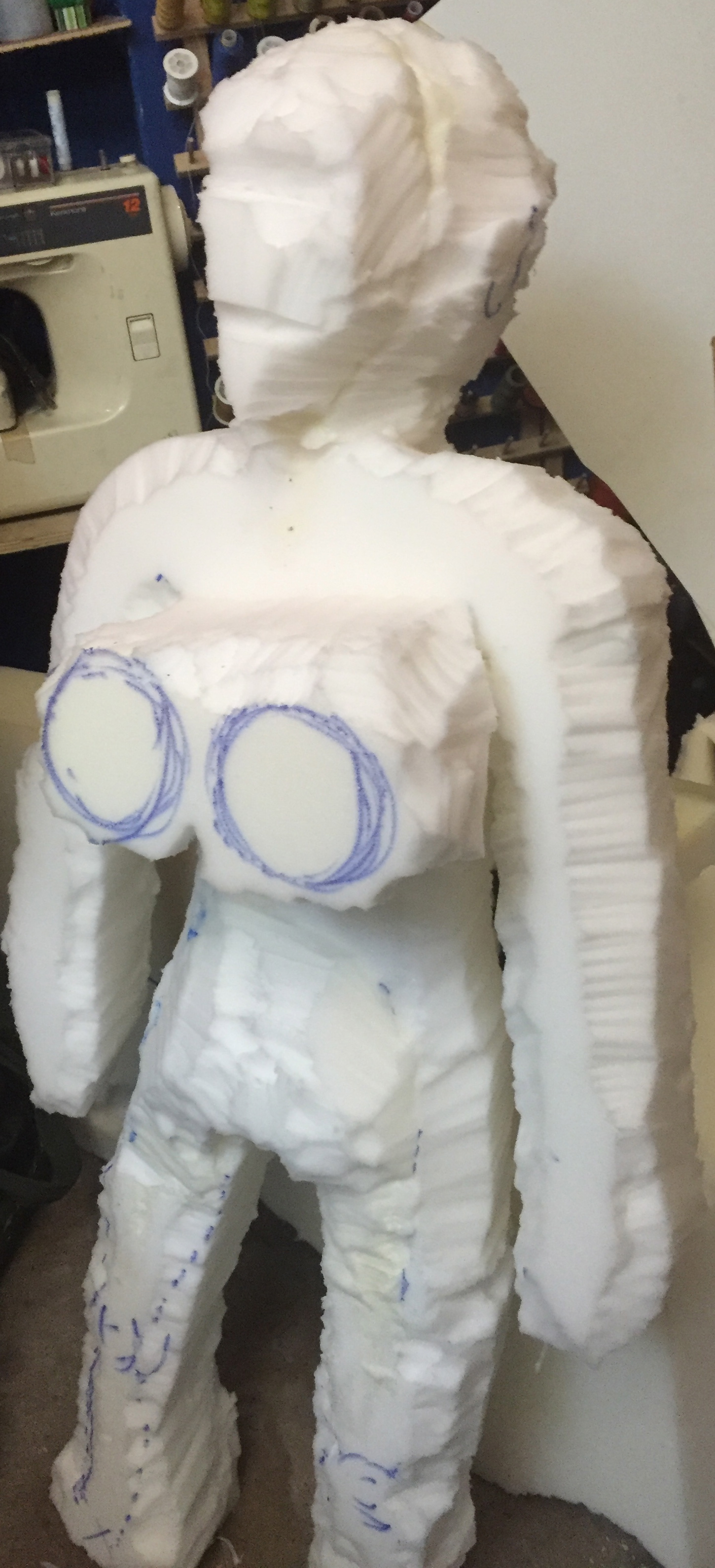

Prior to writing the first draft I experimented with puppets. Some of the puppets ended up in the workshop production, some were created as character and story research, some were based on real people I had met in the field.

First, I built the “brain” of the puppet. I filled the heads with writing, or meaningful objects. I then found the face in the paper, molded the face with tape, covered it with glue, and painted it. Another goal in building the puppets was to experiment with the puppets in performative ethnography. I did this by entering the studio for solo sessions with puppets, text, blank paper, books, and music. When I took the puppets into the studio for a research/rehearsal, the process was daunting for me. It had been years since I’d entered a studio space alone, and I had never entered a rehearsal space as an ethnographer, with collaborators made of paper and tape. I stepped into the studio with the puppets I had made; terrified that too much would happen, or nothing at all. Unlike going to the studio to rehearse a play, I thwarted any agenda with an attitude of exploration, and let go of expectations. It was like letting go of a high diving board and letting the water catch me. Then I translated the studio work onto the page.

Fig. 11. Fig. 12., - Puppets

I started the writing work in intensively in January 2014 and finished this version in June 2015. It culminated in a 3-day workshop production at La MaMa Club in New York that May and a public reading in London in June. This version also exists as chapter four of my dissertation and was written in part as scholarship using historical and auto-ethnographic methodologies- it is part performative ethnography and part pure theatrical script, the theories embedded in the play itself.

It is a 90-minute piece without intermission and with 10-12 puppets.

It merges contemporary spoken word rhymes with imagined ancient rhythms.

It centers on the protagonist (Miri) and her battle with the Academy, which is personified by the character of The Scholar – a puppet. He is a father figure type of villain who tells her she is not worthy of the knowledge due to her romantic notions and lack of intellectual rigor or good sense.

In this version of the play both Abu and the Grave Digger (the roles played by the second actor) exist in Miri’s imagination. With his help (sometimes expressed though antagonism) both in the Middle East (Iraq, Beirut, and Israel/Palestine) and in New York she earns the right to become Aviva in the second part of the play. In this version about two thirds of the play is modern day and one third in history.

An exhibit in the Islamic Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the portal with which Miri finally is allowed to enter the ancient world and become Aviva.

The play ends with Abu and Miri speaking to the audience and is followed by a Poetry Contest and a discussion, encouraging audience engagement in the subject of theatre and poetry as a vehicle for peace (using the example of Muslims and Jews in 11th Century Cordoba). This aspect of the play (encouraging meaningful conversation) is important to me. I (and most of the audience) loved this version, but it felt somehow unfinished and a little messy- also I hadn’t quite found the connection between the contemporary story and the historical one. I needed the right director to partner with. After meeting with Liz Diamond in June 2015 I decided to take a suggestion that came out of our conversation and try a rewrite focusing on the historical part of the play.

Second Version

I worked on this version during a concentrated writing retreat through July and August of 2015. It culminated in a reading at La MaMa Umbria in August. I fleshed out the Cordoba story, left out the contemporary story of my travels to the Middle East. It is a 90-minute piece without intermission and with no puppets. It focuses on the historical story and takes place mainly in Cordoba. This is a play about Abu and Aviva, a real man and woman who lived one thousand years ago.

The play begins and ends with a portal with slides and a lecture podium. A contemporary history professor (Miri) teaches about Ancient Cordoba and a fragment of paper that was found in the Cairo Genizah.

The exhibit at the Met is the last of the slides she shows and features an image Abu in the ancient room. The telling of this story transforms the space and this professor enters history.

At the end of the play (after the Cordoba story) a young man is looking at the same exhibit but instead of Abu Aviva is featured. The telling of the historical story has changed history and put a woman into the center of that particular story.

In Umbria Mia Yoo, the Artistic Director of la MaMa, felt strongly that something was missing, although most of the people present really responded to the play, she missed the urgency of the contemporary story and felt that I (Jessica, the writer/performer) was absent from the telling. After extensive conversations I embarked on the third version of the play – attempting to marry what I loved about the first and second.

Third Version

This version was devised read and written September – November 2015 and culminated in a workshop/ reading at La MaMa in October with Liz Diamond directing.

In this version of the play in Act One the Grave Digger (Ishmael) is a real person that Miri meets in Iraq (he is a poet, a grave digger and a translator). Ishmael is an angry young man who refuses to break his rhyme and raps in part to annoy Miri and in part to express the strange injustice of his life in Iraq. He never stops rhyming. Miri is a puppeteer and a playwright with writer’s block. There is no Scholar in this version, no Academy – her conflict is with Ishmael and with her own Jewish guilt and desires for love.

In Act Two Miri and Ishmael are gone and we follow the story of Aviva and Abu (played by the same actors) where the roles are somewhat reversed – He has writer’s block, she is angry about certain injustices.

The play begins and ends with direct address poems to the audience. In the first poem Miri and Ishmael have no hope for peace, in the last poem at the end of the play, peace might be possible.

I have left the puppets in for now although they are reduced to two - Two puppets she has built or is building of Aviva and Abu as research and discovery for the play she is trying to write and to fight her writers block. A rehearsal process may get rid of them altogether but I wasn't ready for that. I believe this play needs to get done- as the world and its headlines explode a little more every day, and we feel the need for messages of peace. My Heart is in the East is a play that uses poetry to tell stories about love in the present and the past. Audiences have said: “This play is a celebration of language, the language creates the space, I understood that people could live on poetry.” My Heart is in the East is a play that deals with war between East and West, Jews and Muslims, Men and Women. And offers a vision of peace. From recent viewers: “The play ignites our curiosity and desire to learn about the history and lets us dream of a possibility for peace …”.

In Summation

We need devised theatre, Let’s keep doing it.

There are pitfalls it’s hard to do we risk fighting over approach, method, ownership. It’s a practice that requires advanced listening and watching. A deviser must see others, and try things, braving failure and stupidity. A deviser must be willing to be surprised, ho put his/her ego on hold, and most all to be brave. The advantages are endless, but the most important advantage is that by devising, a creator is making something meaningful in a way that teaches us and eventually the world how to collaborate. By constructing collaboratively artists are modeling the means for building peace. A world without Devised Theatre is more ambitious, more competitive, more violent, and lonelier.

.